Bone and Blood – Comanche, the horse who survived

|

I have always been mildly uncomfortable around horses. Growing up in the midwest, I knew people (mostly girls) who either owned horses or really wished they did. Not me. I’d heard too many stories of people getting bitten, stomped or bucked off by one of these creatures. My college roommate’s mother suffered multiple traumatic brain injuries because her otherwise trustworthy horse had gotten spooked, randomly. A horse broke Superman, for crying out loud. Beyond just being deadly, they’re also rather judgy. You have to have a strong and definite idea of what you are doing when you ride a horse, lest it sniff out your lack of authority and toss you into a ravine. A horse is always giving you the side-eye.

As many misgivings as I have about equine-kind, I recognize that there is a significant bond between horses and the humans who ride them. Essentially, riders entrust their lives to the care of this admittedly majestic creature. A friend once explained this to me, shortly after her horse passed away. I admit to feeling somewhat envious of this relationship dynamic – let’s be real, my cat is never going to do anything useful, and certainly nothing along the lines of the partnership that my friend had with her horse.

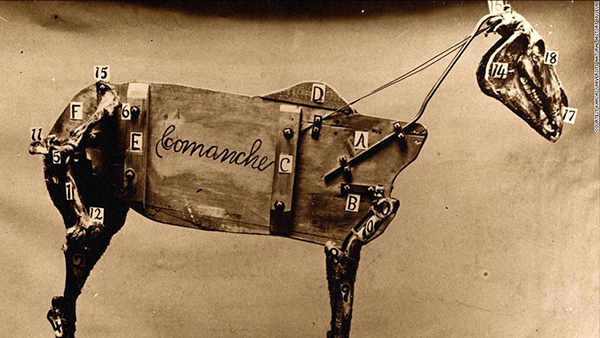

I mused on this as I stared at the well-preserved head of Comanche, a taxidermied horse and a relic of the Battle of Little Bighorn. He stands for posterity, side-eyeing the world from behind glass in the natural history museum at my alma mater, the University of Kansas.

Little Bighorn, for those who have completely forgotten that segment of US history class, was the last great battle victory for the Plains Indians* during the Indian Wars; it is also referred to as “Custer’s Last Stand.” George Armstrong Custer led a small army to attack a coalition of various tribes (Sioux, Lakota, Cheyenne, Arapaho and others); he erroneously thought he had much bigger reinforcement armies coming than he did, among other mistakes. This did not end well for Custer and his men. Against Custer were such figures as Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, who demonstrated exemplary war prowess. Yet, as we all know, in the end this battle really could have been called the Indians’ last stand:

“The Sioux and Cheyenne victory at Little Bighorn in 1876 was a great achievement for Indians, but, with the exception of Sitting Bull’s band, all of the participants surrendered within a year of the battle and were forced onto reservations.”

– James Welch, Killing Custer: The Battle of Little Bighorn and the Fate of the Plains Indians

Comanche the horse is often referred to as “the only survivor” (on the Union side, that is) of Little Bighorn. This is not technically true, for there were many other horses that survived the skirmishes in far better shape than our poor ol’ bullet riddled protagonist; the Plains Indians sensibly requisitioned these. Having no particular use for a horse-shaped colander, they left Comanche to bleed out on the prairie. This is where he was encountered by General Alfred Terry and his troops, two days later. They cleaned him up, nursed him back to health and retired him with honors, decreeing that Comanche would no longer “be ridden by any person whatever under any circumstances, nor will he be put to any kind of work.”

After this crucible, the rest of Comanche’s life was terrific, by either horse or people standards. He lived for another 15 years and was trotted out on tours to boost soldier morale. The soldiers, captivated by his story, fed him “buckets of beer, which he enjoyed.” Comanche, named after another Indian tribe which his owner had been trying to eradicate, became somewhat more than just a horse. In the time after the battle, the story of Custer’s blunder turned into a story of martyrdom. His death provided further justification for the American cause to round up and kill Indians. Along the same lines, Comanche became a kind of mascot for Team Manifest Destiny. If soldiers simply rallied, and held out a little longer in these awful brutal wars, they would prevail and the plains would be theirs.

And it worked. Sitting Bull, who had vowed never to capitulate to the enemy, went from being a victorious and highly respected war chief to a sideshow attraction on Buffalo Bill’s Wild West tour. His people were killed, separated and distributed among various reservations, their children forced into boarding schools in order to assimilate and forget their cultural heritage.

Comanche, on the other hand, significantly outlasted the events at Little Bighorn. When Comanche passed away of natural causes, the US Army commissioned Lewis Lindsay Dyche, regarded as the best taxidermist in the world, to preserve Comanche for future propaganda purposes. Dyche put in a lot of work on this horse, who had healed nicely in the 15 years since being shot full of holes. The army never came to pick up their commission, however, and Comanche was left behind yet again. Dyche didn’t seem to mind this, having developed an affection for his creation – he showed Comanche at the 1893 World’s Fair. (Yes, much like Tupac, Comanche did post-mortem tours).

As I stared at the display, part of me couldn’t help but dwell on the injustice inherent in how well-treated and humanely regarded this horse was, vs. the actual humans whose lives and cultures were decimated by American expansionism. But of course, this is not exactly Comanche’s fault. And us modern-era folk certainly deserve a good helping of some horsey side-eye. For continuing to name our sports teams racistly and commemorate Columbus Day, among other things.

Comanche is a handsome fellow, as horses go, and his expression is almost friendly. Again, as much as any horse could appear friendly. I could see why soldiers would drink buckets of beer with him, and why he attracts pilgrims. The preservation work is certainly impressive. Even up close, Comanche looks like he could be alive, with some not quite fathomable expression in his equine side-eye. Fatigue, maybe? War-weariness? Tour-weariness? Even long-dead, he seems to retain some animation, some sort of latent horse power. The ideas that he represented certainly still do.

* Here I use the word “Indians” for consistency’s sake. A lot of the literature is honestly terribly confusing with regard to the proper nomenclature. From my own conversations with people, it seems as though the preference is to identify a person by tribal name first, then afterwards I have heard either Indian, Native American or First Nation is acceptable. Actually, scratch that – the refrain I heard the most is that the preference is respect above all else, instead of nitpicking about which foreign-imposed label to use anyhow.

Kim Le is a writer and shiftless gadabout who hails from the distant wheat fields of Kansas. Obsessions include sustainability, yurts and extreme DIY. Also, she makes sculptures out of food, mostly potatoes. She never updates her blog at http://badmetaphor.net.

Related Posts: